Over the past year, I have had several clients going through periods of transition. Some have been co-founders who realized that it was time for a more experienced leader to take their business to the next level. Some were just ready for something new. Others have shifted their roles from leader to individual contributor and in one recent case, a CEO-founder sold their company and is now transitioning to a leader within a very large organization. In each of these cases, these were not overnight changes, but rather they were thoughtful shifts that each managed with intention. By transitioning with intention, we are more likely to come out on the other side with more clarity, less stress and with a higher likelihood of success – in whatever way each individual defines success.

The book Transitions, by William and Susan Bridges, outlines the three stages of transition – The Ending, The Neutral Zone and The New Beginning – and encourages the reader to pause and understand each of these phases during their own transitions. This is something most of us do not do with intention – whether it’s ending a relationship, changing a job or transitioning from a household of kids to an empty nest. When it comes to our employment, we have our last day at an old job on a Friday and start our new job on Monday; perhaps taking a week or two in between to decompress. Most people do not have the luxury of long breaks between jobs or extended periods of time to think about their transition before they step into the next thing. Additionally, as Bridges points out, we often don’t see when we are in a neutral zone – that time when we have officially “let go” of who we were before things ended, before we fully embrace the new beginning. Think of it as that time between how you associate yourself with “we”. When you stop saying “at my last company, we…” but you have yet to associate yourself with the “we” of your new role and still refer to your new team as “you”. E.g., “How do you do things here?” It is in this neutral zone where we are truly able to start our transition to a new beginning.

With this neutral zone in mind, I encourage my clients to take a moment – even if it’s just an afternoon – to consider the impact of a transition and what lies ahead. This is usually in the form of journaling where they write their responses to the prompts below and then we discuss them together. Whether or not you have a coach with whom to process your answers to these prompts, you should find journaling your responses to be a useful exercise. You might also consider asking a friend or partner to be your listening guide as you talk them through; be sure to encourage them just to listen and be curious about insights vs. helping you try to solve things.

The prompts below are very career-centric, geared towards startup founders. However, one can easily apply this guide to any type of transition.

Document Your Feels

There is lots of research proving that writing what’s going on in our brains is an important way to process and organize our thoughts. Whether you keep a journal or are just taking a moment in transition to write your thoughts, consider the following:

Highlights & Lowlights

- What are 1-2 highlights from your experience? This could be a memory of your first big product launch, closing a hard funding round or even just that night that all hell broke loose and you fixed a hairy bug at 2am. What made these experiences great? What do you remember about how you felt – physically and emotionally – about these events? How did they motivate you going forward?

- What are 1-2 lowlights from your experience? It could be that one time you really thought the company was dead or when one of your best employees quit because they just couldn’t adapt to the frenetic startup life. What made these experiences awful? What do you remember about how you felt – physically and emotionally – about these events? How did they motivate you going forward?

Learning

- What have you learned as…a leader, partner, employee, peer, innovator, business-person? Most leaders wear many hats and it’s important to use these different lenses to fully embrace all the learnings that came from your journey.

- What specific skills have you developed or mastered? Consider all functions within an organization – financial, sales, product, hiring, etc. These are typically your marketable skills and are often very transferable for the next gig.

- What are you more aware of about yourself that you may not have known at the start of this journey? For example, you may have thought you were not technical, but after having to build your company’s first app because you couldn’t afford to hire a developer, you now know you are more technical than you thought you were at the start!

Evolution

- How have you evolved? Consider phases in your journey – by role or “eras”. For example, perhaps who you were as a strategic leader was very different when you were bootstrapped vs. once you raised your A-round and had a board of directors. Or, perhaps you have shifted in the way you approach the work day as you went from being single to being married with children.

- Who have you become? Think about your key characteristics, your behavioral patterns and attitudes. How is the current “you” different from who you were when you first started this journey? Do you feel differently about things (family, relationships, career) or have changed your reaction to certain situations (more/less triggered, sensitive, focused, caring)?

The Future

- What new tools do you wish to ADD to your toolbox? For example, a product-oriented CEO may wish to learn more about creating a sales playbook or experience venture from an investor’s perspective vs. as the fundraiser. What tools are missing from your toolbox?

- What existing tools in your toolbox do you wish to HONE? For example, a founder may have led a small team and might want to know what it’s like to lead a larger team at scale. Or perhaps you were great at building a social media campaign, but want to learn more about the broader elements of marketing and brand functions.

- What do you wish to leave behind? Consider elements of your role that you didn’t enjoy and that you don’t want to do again (e.g., finance or maybe even management!). Similarly, consider behavioral characteristics that no longer serve you. Were you a micromanager who spent too much time in the weeds? Did you spend too much time on product and not enough time on the rest of your business? Think about what drove you to develop these behaviors, why they did or didn’t serve you in your role and how they will or won’t serve you going forward.

- NOTE: The act of physically releasing things can be very healing. Start by writing a few sentences or drawing pictures on a piece of paper and (safely) burn it or fold it into a paper airplane and toss it from a city window or into the sea. Instead of writing, you could also use natural objects to represent things (e.g., an acorn to represent your tough outer shell or a dried leaf to represent being fragile in certain situations). State your intentions – out loud or in your mind – as you let these things go. What will be different once you let them go?

- What do you wish to teach others? Whether your transition is related to a great exit or awesome promotion or because you feel you failed in some way – your business imploded or you were fired – you have lots to teach others! My father called any learning, even if we failed, “money in the bank”. Take time to reflect on what you learned (above) and how you might be able to mentor others to grow or avoid pitfalls. Not only will this help others following your path, but this will also help you further process your transition.

When journaling the above, I encourage writing full sentences and fully expressing your thoughts around each. Don’t worry about being legible – you may never go back to read them – it is the act of writing that is key here. As you write, look for themes or patterns – do these further inform your transition? Do you see new patterns and/or growth opportunities?

Other Opportunities To Reflect And Reach Closure

If your transition involves others such as cofounders or partners, consider conducting a group reflection process in addition to your individual process. This can be a great way to recognize how the sum is greater than its parts. While each team member played a role in your efforts, it is almost always how the team worked together that led to where you are now. Schedule a couple hours to be together – ideally, face to face and out of the office/home – and share the following with each other:

- Highlights & Lowlights of the work you did together. Consider specific wins you had as a team and what made that work together special. Name one or two times that the team was not at its best. How did these moments affect the trajectory of your business/relationship?

- What are you most proud of as a team? Are there events or elements of your business that could not have happened without the team coming together?

- Key learnings for each individual. Have each person speak to one or two key learnings. It is OK to “+1” someone else’s key learning, but that should not supplant one’s own learnings. Try to acknowledge each of your team members as they cite a learning. “You crushed that big deal. I learned a lot from watching you navigate such a tricky negotiation.” OR “Firing that great engineer who was a bad teammate was so hard. I really admired the way you handled that situation.”

- State what you wish for each other to encourage their path forward. For example, wishing them a great new partnership or a challenging new role.

- Finally, commit to each other. This may be very tactical like committing to getting together once a quarter for beers or a family gathering. Or, it could be committing to supporting each other in their journeys going forward (networking, job reference, a place to crash when they are in town, etc.…).

These prompts work best when they are spontaneous vs. prepared in advance, so I recommend sharing the prompts when you come together. This certainly depends on the type of relationship you have with your partners, but if you are the CEO with co-founders all going through a transition, I recommend you do the above with a facilitator OR at the very least encourage your partners to speak first so as not to bias their reflections. Further, if you and/or your partners have significant others, do not lose sight that they too are going through this transition. A partner who’s significant other is all of a sudden more available than they were when they were running a company, or who is feeling insecure because their partner just lost their job, needs to reflect as much as you do. Make the space for this and include them in any group processes that will serve these important adjunct members of your group.

The New Beginning

You may know exactly what your New Beginning is – e.g., your company was acquired and now you’re in a new role at the acquiring company – you’ve got a new business idea or you have no idea what’s next. When you are unsure about what’s next, it can be easier to think about what you don’t want in your next role vs. what the perfect next role might be. Here are a few prompts to consider for the next thing:

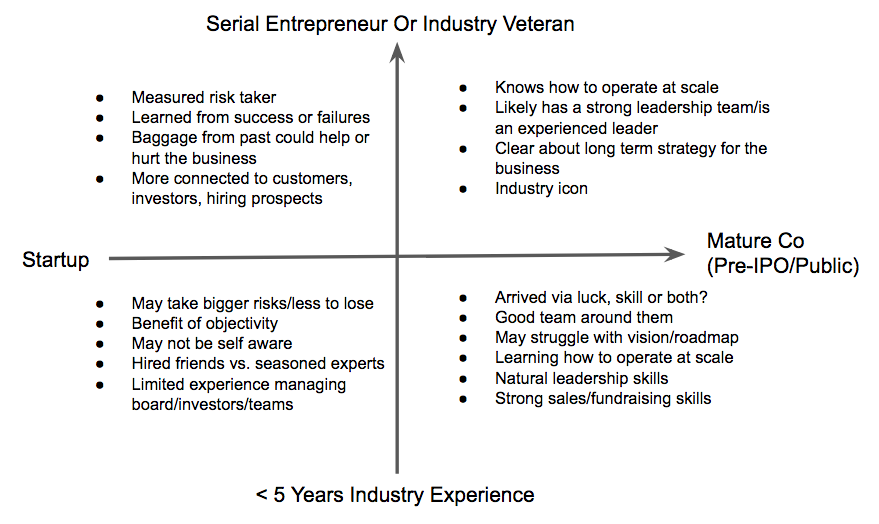

- What types of roles do you know you definitely don’t want? This could be a level of responsibility (e.g., a founding CEO may know they never want to be a CEO again) or within a function of an organization. (e.g., an engineer who became a product leader may prefer to go back to coding).

- What industries are off the table for you? Maybe you spent the last decade in e-commerce and you’d like to try an adjacent area like MarTech or retail?

- What type of people do you prefer to not work with? E.g., extroverts or introverts, micromanagers, jerks, etc.

- What stage of business disinterests you? E.g., does the thought of inheriting a team vs. starting a team from scratch sound miserable? Or perhaps you never want to have to fundraise again.

- What would you have to see in your future role to signal potential? Often, when in transition, we overcorrect for the things we didn’t enjoy in our last role. You may cut yourself off from something you might enjoy based on fear from your past experience. Consider what characteristics are important to you in a new role that may allow you to step into discomfort in an effort to grow and learn.

Whichever route you take, if you have less urgency to get employed ASAP, take as much time (if not more) to consider what’s next as you do with your reflections about what was. I suggest a ninety day period – yes, I know, that may be an unaffordable luxury – where you take at least 30 days to reflect, 30 days to consider your new beginning and then 30 days to gear up for the next thing. Even if you are working through the next thing during this period, try to recognize that you are still in transition and journal new insights as they arise.

Transitions are not always easy and we often don’t give ourselves the time to fully process our endings before we jump into the next thing. Take the time if you can and I am almost certain you will find it helpful. Have you tried other techniques to help you process a transition? Please share in the comments!